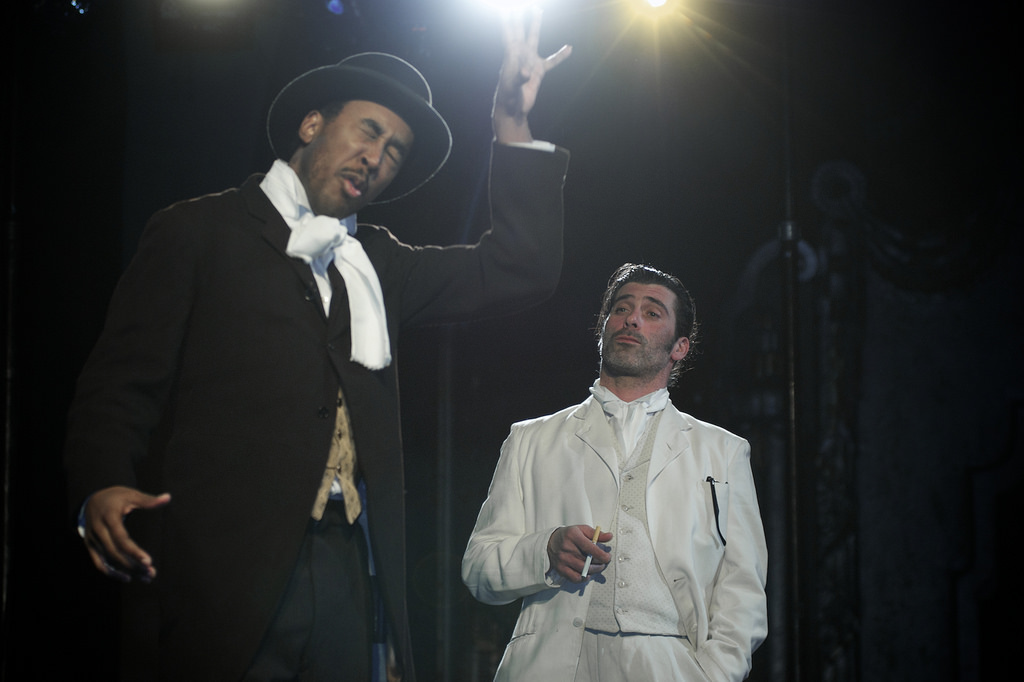

MOLIERE’S

DON JUAN

April 20th- May 15th, 2011

There is no better way to follow Socrates than with Molière’s Don Juan. In Plato’s Apology we experienced the power of the Socratic method: the ability to use a sequence of questions to encourage critical thinking and illuminate ideas. Molière’s Don Juan is a Socratic comedy, asking the big questions, and leaving us to laugh at and ponder the answers.

REVIEWS

“Their production of DON JUAN succeeds marvelously in satisfying their mission.”

- Stage Magazine

ENSEMBLE

John G. Williams

Sganarelle

Ken Sandberg

Gusman

Anthony De Sando*

Don Juan

Jessica Dal Canton

Dona Elvira

Bethany Ditnes

Charlotte

Griffin Stanton-Ameisen

Pierrot

Jessica Dal Canton

Mathurine

Robb Hunter

Poor Man

Daniel Fredrick

Don Carlos

Ken Sandberg

Don Alonse

Griffin Stanton-Ameisen

Mr. Sunday

Robb Hutter

Don Louis

CREATIVE TEAM

Alexander Burns

Director

Neil Bartlett

Translator

Mike Billings

Lighting Design

Jane Casanave

Costume Design

Sound Design

Bryce Page

Fight Direction

Ian Rose

Stage Manager

Pamela Reichen

We all know the story of Don Juan. But what is it that has kept the myth of this womanizing gentleman Spaniard in the cultural consciousness for so long, and why of all the many versions is Molière’s the most poignant for today? The three great forces in conflict in Molière’s Don Juan are sex, religion, and class – three issues that are at the center of our struggle to unify and strengthen America today.

Don Juan is a gentleman, born in to the upper class and willing to use and abuse the privileges afforded to him. Think of America’s over-privileged heirs and heiresses who parade about from sea to shining sea, seemingly above our land’s civil and moral laws, constantly embroiled in sordid tabloid scandals. While we denounce their behavior, we are unable to look away, transforming these individuals into well endorsed celebrities.

Sganarelle, Don Juan’s servant and right hand man, is the play’s moral defender. Despite his best attempts to articulate his beliefs and show Don Juan the path to salvation, he is ultimately willing to jeopardize his own faith for his wages, justifying this duplicity as an occupational hazard.

The Libertine

Don Juan is a Libertine. The root of libertine is “liber” as in free. Originally the word was used to describe the class of emancipated slaves in the 14th century. It was not until the 1560s that Libertine took on the implication of a free thinker, a man who placed the human being at the center of the universe and removed the idea of a proactive God who interfered in human affairs. It took another forty years before Libertine is recorded as having taken on its darker, more licentious meaning.

Unhindered by God’s or man’s laws, Don Juan’s mission is to awaken desire and bring emotional and physical pleasure to as many women as possible. He will stop at nothing to achieve this end. His creditors, his father, his ex-lovers and their families, paranormal forces and even God all attempt to bend the will of Don Juan. Even in the face of death he remains defiant and firmly upholds his credo.

Two of Molière’s most significant additions to the Don Juan story are the episodes with the poor man and Don Juan’s decision to become a Hypocrite. In both scenes Molière isolates moments of crisis in class and faith. Molière wrote Don Juan after his play Tartuffe had been banned by religious authorities and before it had received a single public performance. While his theatre company desperately needed a hit, instead of choosing to write a light hearted romance or delightful diatribe against the medical profession, his aim remained clearly focused on the injustices within the French class structure and on faith as it is manifested through religion.

The Setting

As a work of dramatic literature, the episodic nature of Don Juan and its evolution results in a mash up of cultural styles. Molière moves the romancing Spaniard to the Sicilian countryside, while simultaneously decorating his hero with all the vestiges of the French gentlemen, and surrounding him with an assortment of characters from the French aristocracy to the working class. And when Neil Bartlett first produced his contemporary translation in London in 2005, he isolated the proceedings in a modern hotel room. These many layers of cultural influence are all present in the current production: the original Spanish, Molière’s Italian flavored French, and Bartlett’s British flare. And now we, a band of Americans in Philadelphia, are adding our own layer of 2011 Philadelphianese.

Expressionism is defined as “the presentation of a world through a subjective perspective, radically distorting it for emotional effect, to evoke moods or ideas.” By contrasting different styles of language, fashion, setting and music, and allowing them to work in harmony or in conflict, we are able to explore the emotional and psychological reality of the play in a richer and non-literal space. Through the creation of a modern and stark corridor, the landscapes of Don Juan’s adventures (just like the acts of passion that follow) are left to be filled in by the audience’s imagination. (Our Don Juan lamented in rehearsal one day that as Molière’s Don Juan he never gets to kiss any of the women on stage.) The time period we have chosen is the Belle Époque, an era filled with social morays and celebrated for its healthy appreciation of fashion, romance and passion. From Berlioz to Tchaikovsky, you will hear strains of nineteenth century romanticism throughout, interwoven with the sensual pulse of contemporary electronic music.